A news reporter interviews an elderly shipping magnate:

‘Sir, what is the secret of your success?’

He says, ‘Two words’

‘and, Sir, what are they?’

‘Right decisions’

‘But how do you make right decisions?’

‘One word’

‘and that is?’

‘Experience’

‘so how did you get your experience?’

‘Two words’

‘Interesting. What are they?’

‘Bad decisions’

From the time you and I were around ten years old, up until this moment, our life has been about decisions. All our learning, our values, our capabilities and the value we bring to our jobs – is defined by the decisions that we make.

Research shows that the average person makes over 35,000 decisions in just one day. Some of the decisions are small, and some are big. Many of these decisions will be made subconsciously but some will be deliberate conscious decisions. Since there are so many decisions to make, not acting is also a decision- which usually does not end well- because we simply delay the inevitable. Ignoring a situation does not make it go away but it leaves us with very few options at a later time.

Seafarers too make several high-stakes decisions every day. Plus, they do this in an environment that is constantly changing and unpredictable, thousands of miles away from land. With new technology and faster turnaround of ships, seafarers have not only to be fast and furious but also accurate in making decisions. Of course, we know that not all the decisions made on the high seas end well. there are on average 100 total losses of ships and over 1000 fatalities each year- most of them attributed to human error. This article looks at ways in which we can enable and empower our seafarers, our colleagues and perhaps even ourselves to make better decisions.

It’s easy to get overwhelmed with information required to make a decision, or wait for further information and this can sometimes lead to paralysis by analysis. Both paralysis and analysis are Greek words, and the solution- is also a Greek word.

Heuristics or evretika is a Greek word made famous when Archimedes ran naked around the streets of Syracuse shouting ‘Eureka, Eureka’ or ‘I got it’, ‘I got it’, after he had discovered why objects sink or float. Even today, we explain the flotation of ships through Archimedes principles of buoyancy.

Heuristics today means the distilling of the issue and finding the solution in its most simple and elegant form- which comes about from experience and deep insight. Heuristics are also referred to as rules-of-thumb. Heuristics has been widely researched and recommended in various fields such as aviation and medicine. There is certainly a wide scope for its application in the maritime industry.

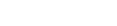

Seafarers have to make several high-stakes decisions every day. Not all decisions end well.

Let’s start with some simple heuristics for anchoring:

- Do not anchor in more than Beaufort Force 6 or above.

- Do not anchor in depths of over 80 metres.

- Do not let go the anchor from the brakes in depths of over 25 metres.

There are several instances of ships which have either dragged or lost their anchors in heavy weather and then grounded on the lee shore with dramatic consequences. There have also been cases where anchor with chain was completely lost after letting go from brake in deep waters.

Good heuristics are not just random numbers but based on science and observation. For example, the IACS rules contain various formulae and statements to specify the operational capabilities of anchors. However, all this information is not readily accessible to navigators on the dark wheelhouse of a vessel at 3’o clock in the morning in rough seas. For decision-making, it’s much easier to remember a rule of thumb which says ‘Don’t anchor in Beaufort Force 6 or above’.

Not all problems, even complex problems need complex solutions. around 80% of all the situations we face are routine and we can build heuristics to enable decision making. Heuristics also help clear up some ambiguity around traditional shipping rules. The collision regulations for instance, talk about things like good lookout, ample time, and good seamanship. Your definition of ample time and safe passing distance could differ from mine; that’s why I recommend that companies should establish heuristics such as:

- Alter course/ speed when at 5 nautical mile range/ 15 minute TCPA.

- Aim for final passing distance as 2 miles in open sea/ 1 mile in coastal waters / 0.5 nm in traffic separation scheme but with escalated watch level.

It’s also quite important to have heuristics for passage planning. Heavy weather is the number one reason for all total losses at sea, for example, the El Faro, the and the Green Lily. Heuristics such as ‘do not enter in wave-heights more than 7 metres’, or ‘do not manoeuvre in ports (unassisted) with wind speeds exceeding 25 knots’, could help mariners make rapid decisions, or at least consult with their offices when the operating environment is outside the normal envelope.

You can have heuristics in the engine room as well - when the oil mist detector sounds, stop the engine. There have been cases where the Chief Engineers have rather opted to change the circuit board, or clean the lenses of the oil mist detector. Surely enough, a crankcase explosion followed, disabling the ship at sea.

Decision making is an important part of our daily activity, both ashore and on the high seas. It’s not always easy as one must often choose between a good option and a better one and with incomplete information. But at the same time, 80% of these decisions are usually routine, or foreseeable and we can plan for them. This is where heuristics help.

In closing, I’d like to recommend two words for you: Heuristics Inventory

Figure out with your colleagues, the various rules of thumbs you can use for your daily operations. Debate them and later formalize the heuristics within your organization- both on board and ashore. Build a heuristics inventory.

Enjoy the eureka moments along the way.

References

This article was also published on the Safety4Sea website