What the commercial shipping industry can learn from the US Navy collisions, Part-2

When I read the accident investigation report, I had a strong sense of déjà vu. My book Golden Stripes- Leadership on the High Seas starts with a steering failure which almost results in a disaster. (Read the excerpt here: Amazon Kindle Preview)

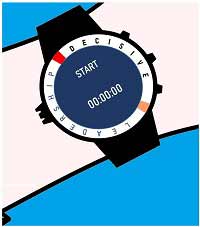

In this case, both the John McCain (JSM) and the Alnic MC (AM) were bound for Singapore from Japan and Taiwan respectively. In the early hours of the morning, each with their commanding officers on the wheelhouse, both ships were proceeding in the same direction of the Traffic Separation Scheme at the east entrance of the Malacca Straits.

Image courtesy: Report on the Collision between USS John S McCain (DDG 56) and Motor Vessel Alnic MC by the United States of America, Department of the Navy

At 0519, the Commanding Officer on the JSM noticed the Helmsman having difficulty maintaining both the course and the speed of the ship. He ordered for the speed control to be shifted to another station so that another watch-stander could follow it up. Inadvertently, both speed control and the helm were transferred to the other station.

At 0521, unaware of the shift of both controls, the helmsman assumed he had lost the steering and informed his supervisor about the loss of steering control.

More confusion followed.

When the commanding officer gave the order to reduce the speed, the watch-stander reduced only the speed of the port side propeller. The starboard propeller was on full thrust which increased the left swing of the naval vessel.

Unintended, the JSM swung rapidly to its port side and onto the AM with disastrous results. The JSM’s bridge team had lost situational awareness and were hardly aware of the collision risk with AM until it was too late. AM, which was only doing 9.4 knots compared to JSM’s 20 knots could do little to avoid the collision.

The time of collision was 0524. i.e. 3 minutes, or 180 seconds after the loss of steering was announced.

Your leadership ‘moment’ could come anytime, and could be short enough to be timed on a stopwatch.

On 15th January 2009, the US Airways Flight 1549 piloted by Captain Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger was safely landed on the Hudson River after a bird strike disabled both its engines. The time between the failure of the engines to the landing was 208 seconds.

In another maritime accident, the tanker Aframax River lost engine control in the narrow Houston Ship Channel. Due to a momentary malfunction of the engine-control governor, the engines were moving astern even through the navigators had given the order to stop the engines. The Chief Engineer bypassed the governor and stopped the engine using the local control- about 180 seconds after the loss of control was experienced. Still the ship’s momentum was high, and despite tug assistance and using both the anchors, the ship struck a shore object. One of the ship's fuel tank was ruptured and a fireball erupted. The Houston pilots, Captain Michael G. McGee and Captain Michael C. Phillips stayed on the Bridge to ensure the burning ship was manoeuvred away from other ships and storage tanks. The fire was finally extinguished about an hour and thirteen seconds later. For their efforts, both the Houston pilots were rightfully awarded the 2017 IMO Award for Exceptional Bravery at Sea. The Chief Engineer also did a decent job in stopping the engines using the local control- though few seconds could still have been shaved off the reaction time - the outcome could have possibly been different.

Ships are often in situations where there is little time to react. And navigators, like in the above cases may not always had simulator-based training to react to every kind of situation. Our responses in that moment are shaped by our experiences, and more importantly- how much intentional work we have put into developing our leadership skills. This is something I’ve put across throughout my book Golden Stripes, concluding with the chapter on decisive-leadership and the DECIDE template.

Decision Making in Crisis Situations

Sully famously said during the air-crash investigation “Over 40 years in the air, but in the end I'm going to be judged on 208 seconds.” This is true for us all- on air, on land, in space, or at sea- these critical moments can be the ultimate test of our professional abilities- as well as the safety of our lives and those under our charge. That’s what leaders are there for.

- Firstly, remember that a crisis can arise at any time. It’s part of your job. Include this aspect in your plans, including in the voyage-plan. JSM could have considered going at a more controlled speed in the congested Malacca Straits which could have allowed for more time for response in case anything unexpected came up.

- Stay alert to detect anything going wrong. The navigators on the JSM should have checked if the steering had indeed failed, and the rudder position instead of simply changing over the steering controls back and forth.

- Take positive, strong action. Have heuristics in place for such events (refer Chapter 20 of Golden Stripes). The navigators on the JSM should have immediately stopped both engines while they engaged the back-up steering system. The Houston Pilots on the Aframax River and Capt. Sullenberger on US Airways Flight 1549 did all the right things to prevent a bad situation from turning worse.

- Train individually and as a team for such events. The supporting members of the Bridge Team on the John McCain should have turned on the AIS and alerted all traffic in the vicinity about their predicament. This could have prompted the tanker Alnic MC to take avoiding action. Each member of the team must collectively swing into action because when an emergency strikes, you're on a stopwatch, and you’ll all have to respond in seconds.