HARBOUR MANOEUVERING PLAN (HMP)

Rethinking the shared mental model and improving the integration of the Bridge Team with the Pilot

The traditional Master-Pilot exchange is no longer fit for purpose!

This two-page form seldom offers any value to a Harbour Pilot who brings similar ships in and out of times at least half a dozen times each day. it does not offer an ideal template for discussions between the Pilot and the ship's navigators.

For example, on 4 May 2017, the 363-metre-long, 11,400teu container ship CMA CGM Centaurus made heavy contact with the quay and two shore cranes while executing a turn under pilotage during its arrival at Jebel Ali, United Arab Emirates. The accident resulted in the collapse of a shore crane and ten injuries, including one serious injury, to shore personnel.

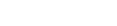

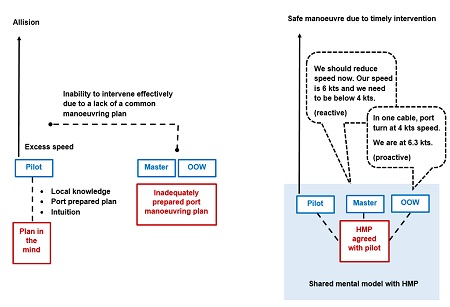

The UK Marine Accident Investigation Branch (MAIB) investigation established that CMA CGM Centaurus was going too fast (6.3 knots instead of 4 knots) for the intended manoeuvre when the pilot started the turn. The pilot was aware that the ship might have been travelling a little faster than he would have liked when he initiated the turn but was content that the ship would be able to complete it. The pilot’s performance was focused on getting the ship as quickly as possible to the berth; this influenced his decision to turn the ship into the basin without ensuring that the manoeuvre was conducted at a sufficiently slow speed to enable its safe completion. Still, following the accident, the pilot expressed surprise on learning that the ship had been making 6.3 knots when he ordered the turn.

After the accident, manoeuvring trials were carried out at the shipping company’s bridge simulator training centre in the presence of the MAIB. A simulated reconstruction of the manoeuvre confirmed that the CMA CGM Centaurus could not complete the turn if the turn was commenced at 6.3 knots. Further simulations showed that a direct turn into the basin was achievable without tug assistance if the turn was started at a ship’s speed of up to 4 knots and the bow thruster on full power to port.

The ship’s bridge team were uncertain of the maximum speed required to complete the turn safely. The master did not ask the pilot when he boarded how he intended for the CMA CGM Centaurus to approach the berth.

There was no agreed plan for the intended manoeuvre, and therefore no shared mental model between the bridge team and the pilot. Consequently, the pilot was operating in isolation without the support of the bridge team, allowing the pilot’s decision-making to become a single system point of failure.

Extract from the MAIB Marine Accident Data Analysis Suite (MADAS) showing the CMA CGM Centaurus make contact with the pier at high speed

Extract from the MAIB Marine Accident Data Analysis Suite (MADAS) showing the CMA CGM Centaurus make contact with the pier at high speed

Both the master and chief officer on the bridge were over 55 years of age, with rank experience of over 10 years and experience on this size of ships. Both had completed ship handling, and maritime resource management training courses. Despite their experience, neither officer felt able to determine with confidence that the ship was proceeding at too high a speed at the start of the turn to be able to complete the turn safely. Consequently, the pilot’s decision to turn at a higher speed was not effectively challenged because the ship’s bridge team lacked the necessary knowledge and experience to be able to confidently intervene and correct the pilot’s action.

The MAIB recommended that pilots and ships’ bridge teams work together and implement the best practices of bridge resource management to ensure the safety of both ships and ports. However, the MAIB report stops short of recommending clear steps and leaves it to the industry to come up with an alternative.

An industry problem

Despite two decades of safety accident investigations and recommendations, similar accidents continue to recur. A survey by the Australasian Marine Pilots Institute and the New Zealand Maritime Pilots Association indicated that visual piloting combined with local knowledge and the pilot’s intuition is considered sufficient by pilots. Evidence obtained from voyage data recorder and vessel traffic services recordings shows that little has changed over the years. Common features in recent accident reports based on irrefutable evidence are:

- Inadequate passage/pilotage/berthing plan (turns not planned).

- The absence of a shared mental model leading to a lack of involvement of the bridge team.

- Over-reliance on visual navigation, local knowledge, and pilot’s intuition.

- It is extremely difficult to recognise a loss of situational awareness without a reference (pilotage plan).

Instead of waiting for the industry to discuss and reach a consensus, in all humility, I'd like to propose the alternative, a best practice called the Harbour Manoeuvering Plan (HMP)

The HMP can replace the old MPX if used effectively. For comfort, use both.

To address the issue of shared mental models/reference/pilotage plan, we introduced a best practice in our controlled fleets called the Harbour Manoeuvring Plan (HMP), which resulted in a drop of over 80% in groundings and allisions.

We first analysed the passage plans of the ships and compared them with what was being executed consistently when they arrived or departed ports. As with the CMA CGM Centaurus, we discovered that most ships did not plan the speeds for manoeuvring in the harbour, and the plan lacked critical detail. The ship and the onshore marine team then prepared manoeuvring plans for each port, for each size of the ship in our fleet. The project lasted a year, during which the ship’s navigators were trained in the use of the plan.

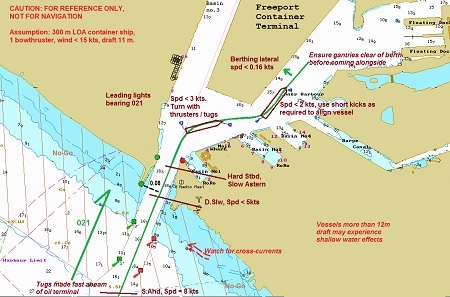

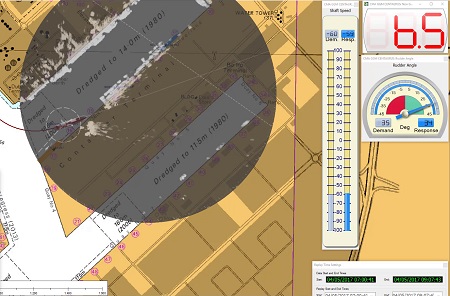

HMP is better implementation of SOLAS: The HMP is essentially the ‘passage plan’ that the ship’s navigators are required to prepare anyway under SOLAS Chapter-V and IMO Resolution A.893(21)-Guidelines for Voyage Planning, but with increased attention to detail. The HMP calculates realistic speeds, wheel-over point, and rate of turn for each leg of the manoeuvre in port, especially for turns, based on the ship’s manoeuvring characteristics such as turning radius and momentum. The plan also takes into account local regulations such as the speed to avoid wake damage to other ships and shallow water effects. Inputs from other ships such as currents at the breakwater or near the berth, areas of heavy traffic, usual tug engagement point, and other functional (but not cluttered) navigation information are included in the plan. The HMP also contains photos and satellite views of ports to help the navigators develop a mental model of the port and the planned manoeuvre. The HMP is kept realistic and up to date with constant inputs from the ship.

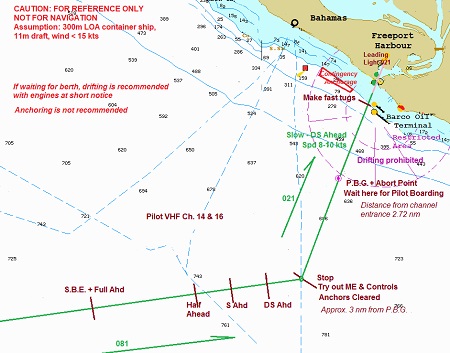

Sample HMP for berthing at Freeport, Bahamas container terminal

Sample HMP for berthing at Freeport, Bahamas container terminal

Sample aerial photo for Freeport, Bahamas harbour. Photo courtesy: Freeport Harbour Company

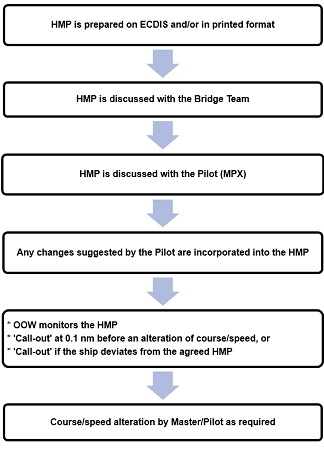

Step-1: The HMP is prepared on the ECDIS; optionally, two colour copies are printed on A4 sheets for ease of discussion, first with the bridge team and then with the harbour pilot.

Step-2: The HMP becomes the primary objective of the Master-Pilot Information Exchange (MPX), with the Pilot Card used as a reference for any ship specific information. The master would typically say, “Mr Pilot- here’s our plan for the manoeuvre. Please advise if you have any comments. Particularly, do you think the speed at the start of the turn here should be 3 knots?”

Any changes to the ship’s HMP due to prevailing weather conditions or change of berthing position are discussed with the pilot before commencing the manoeuvre. With this, a shared mental model is available to the bridge team.

The project was not without its challenges. It is a time-consuming process, and requires different levels of review and good ship-shore and fleet-wide information sharing. My argument has been that the plan is required by SOLAS anyway; we might as well do it effectively and not treat the ‘berth-to-berth’ passage plan as an exercise for third-party inspectors.

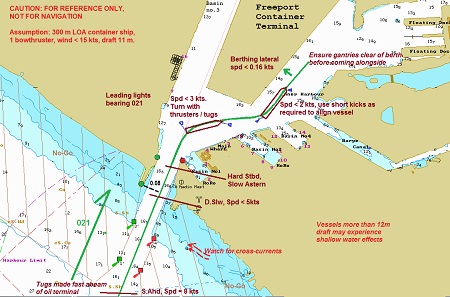

The HMP is not a novelty: Several cruise ships use them; however, it is still not widely used by cargo ships. Port and pilotage services in Australia and New Zealand are a step ahead— they have a version of such plans on their website. They are also working on getting these plans sent to the ships before their arrival, so that the plan may be imported to the ship’s ECDIS. Such initiatives are already included in Bridge Resource Management Courses in Australia and New Zealand and some training centres in Europe.

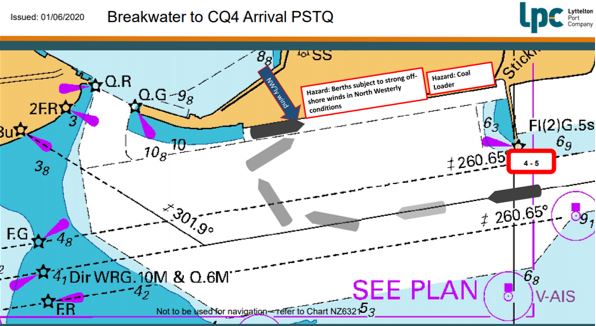

A sample manoeuvering plan used by Lyttleton Port Company, New Zealand

A sample manoeuvering plan used by Lyttleton Port Company, New Zealand

HMP for port approaches

You will see below that the HMP is not only for the manoeuvre from the pilot point to the berth but also for arrival to the port. Markings include detailed manoeuvres that involve slowing down to enter the port, cautionary notes regarding anchorages and areas with a history of collisions to help the bridge team be aware of and prepare for the challenges. A similar plan is also prepared for departure from port.

Sample HMP for approaches Freeport, Bahamas

Sample HMP for approaches Freeport, Bahamas

The UK MAIB report on the grounding of the Maersk Kendal off Singapore in 2009 showed that speed was excessive and uncontrolled before the grounding. Both the master and the chief officer had lost situational awareness, which also meant that the chief officer did not alert the master of the imminent danger of grounding. The report also found that the manoeuvring plan lacked crucial detail which meant that none of the navigators on the bridge had a shared mental model for the manoeuvre into Singapore. On other ships that I audit, I often see unrealistic speeds marked in the passage plan table or marked as ‘various speeds’. Even if the speeds for manoeuvring in the harbour are realistic, they are seldom transferred to the ECDIS. So how would the navigators have agreed on the speeds and critical points to watch out for?

Using the HMP to enable meaningful MPX and subsequent interventions

The HMP process does not stop at preparing the plans and the MPX.

Step-3 of using the HMP requires that the Officer of the Watch (OOW) assisting the master and the pilot is also assigned to ‘call out’ one cable (0.1 nautical mile) before each action point, or at the action point if the planned manoeuvre is not executed in time. This critical step addresses the mental disconnect, and any power distance issues that have been observed among OOWs on the bridge supporting the master and the pilot. Now equipped with an agreed plan, the OOW’s role in the bridge team is more proactive than reactive. The OOW has more confidence to intervene if the pilot or master delays initiating a turn or reducing the speed per the agreed plan.

Typical process/communication flow with the HMP

Typical process/communication flow with the HMP

A different approach with the HMP allows timely interventions

Change is Difficult: When we first introduced the HMP, the ship’s navigators were apprehensive that the ‘call out’ might irritate the pilot (or even some ‘senior’ masters). Unfortunately, some harbour pilots do not engage well with the ship’s navigators, one of the reasons being that the previous forms of MPX did not provide for a meaningful exchange of information. When agreeing on the manoeuvre, the master and the OOW can also agree with the pilot if the ‘call out’ should be before the planned alteration of course or speed, or only in case of a deviation from the plan. But this step is essential to engage the OOW in the bridge team and keep them situationally aware during the manoeuvre. When a large container ship is to turn in a congested harbour, a call-out “in one cable, we turn to port at a speed of 4 knots – we are currently at 6.3 knots” provides a timely and confident reminder when even a ten-second delay could lead to an incident.

An International Group of P&I Clubs (IG P&I) study found that an incident occurred every week on average for over ten years on a vessel navigating with a pilot on board, and 60% of these accidents are allisions. The average value per incident is approximately US$1.74 million. The IG P&I recommend developing an internationally standardised approach to the Master-Pilot Information Exchange that emphasises the visual presentation of the pilot’s plan for the pilotage during the MPX and discourages reliance upon a purely verbal exchange of information. The International Maritime Pilots Association (IMPA) is working actively on this feedback.

Meanwhile, and to supplement the pilots' efforts, the ships' use of Harbour Manoeuvring Plans will help increase situational awareness and bridge team integration during navigation in ports. A shared vision of the manoeuvre and working off the same plan with the pilot is essential to a well-executed port transit.

Perhaps an HMP such as the one below could have helped the CMACGM Centaurus avoid the accident.

References

- Marine Accident Investigation Branch, Report on the investigation of heavy contact with the quay and two shore cranes by the UK registered container ship CMA CGM Centaurus at Jebel Ali, United Arab Emirates 4 May 2017, Report No 17/2018, © Crown copyright, 2021.

- Australasian Marine Pilots Institute, Webinar - Port & Pilot supplied ECDIS routes and passage plans, 11th February 2021

- International Group of P&I Clubs, Report on P&I claims involving vessels under pilotage 1999-2019

- Marine Accident Investigation Branch, Report on the investigation of the grounding of mv Maersk Kendal on Monggok Sebarok reef in the Singapore Strait on 16 September 2009, Report No 2/2010. © Crown copyright, 2021.