The maritime industry is one of the most international environments. A ship could be owned by a corporation in Greece, flagged in the Marshall Islands, classed by a Japanese society, audited by a Norwegian society, with technical managers in Singapore, chartered by a commodities trader in Switzerland, and crewed by a multi-national crew of Europeans, East-Europeans, Indians, and Filipinos. A commercial ship will call ports worldwide from Chile to Belgium to Mozambique to Dampier, pass the Suez and Panama Canals, and perhaps drydock at a Chinese yard. Maritime professionals engage with people from different cultures- an Argentinian shipper, a Moroccan receiver, a Saudi pilot, a Chinese ship repair manager or call an equipment manufacturer in Germany to assist with troubleshooting.

How do you then communicate and lead effectively in such an environment? Multicultural sensitivity, an inclusive outlook and an awareness of bias are very important in the maritime industry.

I was born in India, but I have travelled the world since I was seventeen and lived in Hong Kong and Cyprus, and I can proudly say that I am friends with as many non-Indians as with Indians, and I will call some of my international friends as close as a brother and sister.

I do have emotional bonds with India, but I prefer to think, speak, and act on my love and my duty towards humanity, all living beings, and my profession. I have sailed and worked with nationals from many nations, even from states with difficult relationships with India in the past or present; even though it has been many years since I was obliged to share a professional relationship with them, we became, and remain friends. Seafarers are typically a busy lot and don’t have time for drama; even then, they are a creed that looks out for each other.

My life at sea shaped my outlook as a global citizen, neither looking down on anyone nor looking up to anyone; that has helped me as a maritime professional and as an individual. Most of my experiences have been pleasant but there have also been challenges.

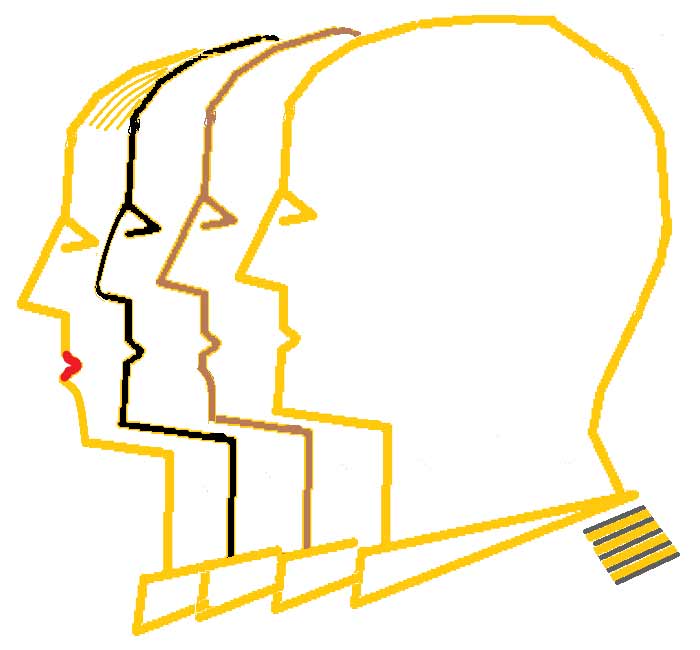

Seafaring is a shining example of a multi-cultural background working well. This is one of the many concept drawings for the cover of my book- Golden Stripes - Leadership on the High Seas

Whether it’s a professional or social interaction, it is an uphill task if one is not from the same background as the majority. The ugly manifestations are when ‘normal’ work conflicts and professional rivalries descend into unpleasant attributions to one’s ethnic identity. I’ve seen onshore maritime executives who, despite many years of ‘experience’ make comments regarding seafarers of different nationalities:

‘Why do these guys need to go home for (…) festival/season’

‘Why do these (…) guys eat so much?’

‘Why can’t they eat the normal stuff like everyone else?’

‘These (…) guys are not as good as (…)’

At the extreme, I’ve heard statements such as ‘you (…) are always like this, or ‘you f**king (…), or a sarcastic ‘why don’t you stay at where you’re from’

It is clear that such behaviour is unacceptable in any modern workplace and is subject to disciplinary action. However, laws alone cannot change mindsets; discrimination is also practised at a covert, subversive level. Examples include passive aggression, ignoring a person, speaking in a different language when others don’t understand it, favouritism or biases when awarding opportunities (similarity bias), and having different standards of behaviour for different persons. Such behaviours are cultural or individual prejudices, usually based on fear of the unknown or unfamiliar, but I would like to think that thankfully the maritime community has less discrimination than other industries.

Effective global leaders need to be culturally competent. This is not just a nice to have, but a must-have to be able to harness the potential of talent irrespective of gender, ethnicity, nationality, sexual orientation, or age. People from varied backgrounds have unique perspectives and it makes the organization richer with insights, ideas, and energy levels.

It’s also self-serving to be culturally aware. As a crewing manager, I noted that when East Europeans wanted to spend their summers at home, I could fill those positions with Asian seafarers and when South-East Asians wanted to spend their festival season (typically in Autumn), I could fill those positions with East-European seafarers.

In another instance, when I was a safety manager in my early thirties, I was approached by a chief engineer who was already in his late fifties and wanted to become a superintendent. Usually, most seafarers make their transition to shore in their thirties or early forties; any older and corporate openings become scarce. However, assessing his potential, I recommended to my board that he be employed. I’m still proud that I supported him as he delivered value to our organization that exceeded our expectations. He recently retired after a productive fifteen years ashore.

Multicultural leadership is not about presenting an insincere smile or putting up a front or a hire to tick a box. Accepting diversity is authentic and needs to be expressed through our thoughts and actions. However, despite our good intentions, here are some skills that are helpful when interacting with any nationality:

Be patient. English is not the first language for all. Speak slowly and clearly. Give people time to express themselves and don’t judge their competency by the speed of their speech.

Avoid jargon or phrases that the listener may be unfamiliar with. Don’t drink the Kool-Aid!

Be respectful. If you’re not aware of the nuances of the culture, being genuinely respectful will prevent you from making a business-threatening error. If you do realise your mistake, you can always apologize and laugh it off! Don’t ever shout and insult anyone – that’s not acceptable in any culture.

Dump old-world narratives where certain cultures were considered superior or untrustworthy. Dump even the cultural references such as 'gwailo', 'gora', even in your mind. It's the mindset that needs to change- inclusivity is not about putting up a front. In some cultures, men are not accustomed to a woman colleague or boss. Thankfully, the world is increasingly including the woman talent pool. I must quickly add that women, besides their intellect, also bring a greater sense of empathy in the workplace, and we're richer for that.

Respect personal space. During a navigation audit, I observed an Asian Captain who in an attempt to build rapport with the European Pilot touched the latter’s elbow. The Pilot bluntly rebuffed him ‘Captain, please don’t touch me- I’m not your friend’. Men who've had limited interaction with women other than family members are caught off guard when women from other cultures appear friendly; they sometimes mistake friendliness for sexual advances. Err on the side of caution.

Speak as you must. In our early childhoods, we’re taught to be good boys and girls. Some national cultures further deepen the deference to authority which leads to a high-power distance. For example, an officer-of-watch of any nationality may find it difficult to challenge their captain or a harbour pilot’s action. But the instance of such deference may be more so in Asian and East-European seafarers than in say, a Scandinavian one. You cannot afford not to speak as this directly affects the safety of the ship and its crew.

Listen. On the other side, officers in senior positions must be aware that seafarers in lower ranks from certain nationalities may be reticent to speak out and silence does not always mean agreement; be aware of the nuances of body language, make efforts to build trust and to elicit feedback. Not listening to safety concerns can have serious consequences, as it happenned on the Bow Mariner. In some cultures, if you offer a drink, the first response is to say ‘no, thanks’ even if they are thirsty, so insist. I think everyone appreciates if you ask that extra ‘is there anything else I can do for you’

Don't mix politics with work. Don't carry historical or political baggage. Have a strict rule of not discussing national or political issues in the workplace. Especially in today’s world where we’re bombarded by media with a host of divisive issues, one’s opinions are one’s opinions and not everything needs to be shared.

Create your organizational or ship’s culture that is so strong that it can and must be the practised culture at work, irrespective of where the employee or seafarer is from. Have a strict rule about non-tolerance to discrimination. Reinforce the culture by walking the talk, ensure rules are followed by everyone, and be fair.

On a personal level, travelling across different cultures, reading books or watching movies from different languages - helps us understand that we're all the same, we want the same things in life, to work, provide for our families, and achieve our potential. You may also want to remember that the genetic difference between individual humans today on average is only about 0.1%. In fact, the DNA of today’s humans is more than 95% similar to chimpanzees. But compared to chimps, humans have an advanced prefrontal cortex which can make logical rationalizations instead of relying on evolutionary cognitive and emotional biases. You can start by being aware and training yourself to overcome these biases, that is if you would like to be known as a culturally competent, and likely, a successful maritime leader.

References:

The Hofstede Cultural Dimension Index

The Impact of Seafarers’ Perceptions of National Culture and Leadership on Safety Attitude and Safety Behaviour in Dry Bulk Shipping, paper by Chin-Shan Lu, Chen-Ning Hsu, Chen-Han Lee

Cultural diversity, manning strategies and management practices in Greek shipping, Ioannis Theotokas and Maria Progoulaki

Managing culturally diverse maritime human resources as a shipping company’s core competency, Ioannis Theotokas and Maria Progoulaki