If you love your workspace, you’ll love your work a little more – Cynthia Rowley

In early 2002, I was the chief officer on a 6-year-old 50,000 deadweight woodchip carrier. The ship was built at a sophisticated Japanese yard, for a large shipowner, and chartered to a major shipping line. I always admired the beauty of the design when we loaded woodchips of the maximum allowable specific gravity for its conveyor belts, the cargo holds were full by volume, as well as the ship was down to its load line marks. Perfect efficiency.

Except when it came to the living quarters.

When I lay down on my narrow bed, I could see the frames and piping on the deckhead above me. The cabin was cold in winters, and with a bare cabin around me, felt colder. I felt so miserable in the cabin that I was in there only to sleep and shower; all my other waking hours were spent at work (perhaps this was the reason for the design?). The ratings had no individual washrooms but had to share a communal bath. The officer’s lounge was small, dark, and uninviting. The only redeeming feature of the accommodation was the ample gym room next to the valve solenoid room on the lower deck. We could play ping-pong after work during the long Pacific crossings.

Almost ten years later, I was in charge of a new-build project for a ro-ro ship at a Chinese yard. The owners who had commissioned the ship ran into financial difficulties and sold the project to our company. The ship was almost finished and the final outfittings were in progress. At the stage we were in, we really couldn’t make many changes to the design as we would risk not making the delivery date to the charterers. The ship was well designed, except when it came to the accommodation. Despite the ample space on the top deck for the living quarters, the cabins were small. The bulkheads and decks were painted steel. Even on the new ship, you needed pedestal fans to feel comfortable in your cabin in hot weather. Not an iota of warmth or comfort- even refurbished shipping containers are more comfortable.

But it has not always been like this.

I was the chief officer on a Japanese 1982 built crude oil tanker where the cabin was with a plush carpet. There was an office and a well-appointed bedroom. For most of the time, the ship was employed on shuttle tanker operations which meant I didn’t have the time for lying in the tub, but it was good to have a spacious bath.

A better example of a captain's office and dayroom

Later I was master on an even older 1977 European built container ship. The living quarters were tastefully furnished and comfortable. Maintenance on deck and in the engine room was challenging; we had breakdowns almost every day and we worked long arduous hours. But after work, when the crew came back to the living quarters, it was as if they had entered a different space. The bar, the games room with foosball and darts provided a good setting to relax and be refreshed by the next day. There was a sauna and spacious gym for the crew to maintain their health. Cabins were spacious enough so some of the officer’s families could join them for a few months at a time.

So, why has the quality of living quarters deteriorated while we have spent money to maximise the cargo intake on the ship and make them more fuel-efficient? It almost feels as if seafarers are being punished for working on the ships. Is it because the seafarer nationality is no longer the same as the shipowner that it creates indifference? Or is it the fact that most seafarers are from developing nations where it is assumed that they have lower standards of living back home, that no thought needs to be given to their comfort onboard their ship?

An officer's shower cum laundry on a chemical tanker

I offer another view for stakeholders: on the old ships that had better living quarters, the crew were happy. They didn’t complain if their reliefs couldn’t be executed on time, they didn’t complain about the work, they even looked forward to coming back to work on these ships. The crew were well-rested and approached their work with enthusiasm and initiative. These are all appealing to any shipowner who wants to create a dedicated crew pool for their ships. Why are we as a maritime industry axing ourselves in the foot by being callous about the quality of living quarters on the ship?

Not every shipowner is indifferent though. A Singapore based large shipowner has developed a project to re-imagine the living spaces on their ships and have created more conducive environments to rest, eat and socialise. Some large European shipowners have invested in good quality accommodation, even with inbuilt hi-fi speaker systems.

The shipping industry is currently guided by the ILO Maritime Labour Convention, Classification Society, and Flag State standards but these are the minimum standards that cover basics such as size, vibration, noise, indoor climate, and lighting. Some of the studies into crew accommodation are prompted by a study into crew fatigue and accident prevention. Shipyards focus on the accommodation standards more for passenger ships and survey vessels but not so much for run-of-the-mill cargo ships which carry over 90% of world trade. Recently, the IMO passed a resolution reducing the noise levels in the accommodation to be reduced by 5 decibels or 56% from the previous levels.

Yes, the shipping industry has put its collective head into it and has developed some very good, helpful guidelines. But not everyone has put their heart into it, and it shows in the quality of the living quarters. My friend who is a captain on the latest generation of ultra-large container ships confirmed that now all crew cabins have an attached bath and toilet. Hot water and air conditioning have improved. But the sizes of the rooms have gotten smaller to the bare minimum MLC requirement. Even functional comfort has suffered. Common rooms like lounges, smoke rooms, mess rooms, conference rooms are reduced drastically in size, so much so that there is not a single place in the accommodation where all the ship’s crew can be accommodated for a meeting or a social event. During safety meetings in the mess room, half the crew has to stand. Researchers complain that seafarers don’t socialise or communicate enough, but where is the space for such activity?

Storerooms in the accommodation, such as for provisions and linen have reduced in size and number. These rooms can let only one person inside the room stand, pick up what you want and get out. On some ships, the provision rooms are so small that you cannot store sufficient food safely for long voyages.

Overflowing shelves of a ship's dry provision store

Shipowners and insurers expect the seafarers to be fit at all times to handle mooring ropes or climb into tanks, but the facilities provided to maintain physical health are not fit for purpose. To ‘comply’ with the MLC, there is a game room for ping-pong, but you can hardly move around the table – which means it’s not used at all. On many ships, there is no room for basic gym equipment such as a treadmill or an elliptical. Swimming pools have become history. We’ve seen crew construct their own gym in the noisy steering gear room. That’s not a great situation to be in.

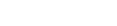

Seafarers need to work with both their minds and heart to be safe, efficient and engaged at sea. Shipowners, shipyards, and regulatory bodies need to put their hearts in it too. Let’s move the needle on crew habitability from just physical comfort to functional comfort and psychological comfort. A leader’s role includes providing a safe and efficient environment for their people.

Providing high-quality crew accommodation has been identified as a key factor in improving mental health at sea, but these recommendations will remain unfulfilled unless shipowners collectively demand that shipyards provide comfortable living spaces for their seafarers. We have to remember that the ship is the crew’s home for extended periods of time, ranging from 4 to even 9-12 months at a stretch. Especially during the pandemic, seafarers have not been able to go on shore leave, and have had to stay on board for extended periods; it is all the more important that they have a comfortable space to live and work.

Shipyards can also pride themselves on the quality of the crew accommodation, along with the eco notation. Invite interior designers and behavioural scientists to provide inputs on how the living quarters can be designed. Shipyards and contracting owners should remember that several features of interior space have been shown to affect social interaction and relationships, and the presence of natural elements contributes to recovery from stress. Creating obvious, easy, and attractive opportunities for physical activity, relaxation and positive social interaction may stimulate desired behaviour through ‘nudging’. These should be part of the ESG initiatives of the industry.

There is scope for research on components of crew living quarters that can be improved to facilitate functional and psychological comfort, and in turn, the quality of life onboard. Research suggests that happiness and a feeling of well-being result from a good quality of life.

My call to action also includes a message to seafarers. Take care of your accommodation. On one of the old ships that I was a master on, I worked with the superintendent to invest a significant sum in upgrading the accommodation. We changed all the upholstery on the chairs and sofas, changed all the curtains and cabin carpets and repaired broken furniture. A year later, I visited the ship as a superintendent. My heart sank. The carpets were stained with dirty boots. The seats in the mess room were dirty. I found out that cabin inspections were only done on paper and there was very little attention given to the living quarters. I was not surprised when the condition of the deck and the engine room had also deteriorated drastically since I was last onboard.

Something which I found myself doing on almost other ship I sailed on was repairing the ‘pilot chair’ on the bridge, and the chairs in the engine control room. These chairs for me symbolise something important, signifying positions of great responsibility in taking care of a multi-million-dollar ship and the cargo, and the lives of the crew members. To my dismay, I often found them torn with the foam underneath protruding. Not being able to stand it, I would usually repair these chairs as a matter of priority- even with my rudimentary canvas sewing skills.

The ship is a home away from home for seafarers. The right living environment can provide the crew with much-needed rest and motivation to put in another good day of work. Research shows that our work and living spaces make us feel uncomfortable and ill-at-ease, energetic, and stimulated, or relaxed and at peace. That in turn affects our quality of work, safety, and efficiency at sea. It’s not that hard. We just need to collectively put our hearts into it!

--+--

References:

ILO Maritime Labour Convention

IOSH, Seafarer's Mental Health and Well Being